On March 23, 2010, President Obama signed the Affordable Care Act (ACA) into law, marking a significant overhaul of the U.S. health care system. Prior to the ACA, high rates of uninsurance were prevalent due to unaffordability and exclusions based on preexisting conditions. Additionally, some insured people faced extremely high out-of-pocket (OOP) costs and coverage limits. The ACA aimed to address these issues, though it did not eliminate all of them.

The ACA affects virtually all aspects of the health system, including insurers, providers, state governments, employers, taxpayers, and consumers. The law built on the existing health insurance system, making changes to Medicare, Medicaid, and employer-sponsored coverage. A fundamental change was the introduction of regulated health insurance exchange markets, or Marketplaces, which offer financial assistance for ACA-compliant coverage to those without traditional insurance sources. This chapter has a special focus on these Marketplaces that are integral to the ACA’s framework.

A key goal of the ACA was to expand health insurance coverage. It did so by expanding Medicaid to people with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (the poverty level in the continental U.S. is $15,060 for a single individual in 2024); creating new health insurance exchange markets through which individuals can purchase coverage and receive financial help to afford premiums and cost-sharing, in addition to separate exchange markets through which small businesses can purchase coverage; and requiring employers that do not offer affordable coverage to pay penalties, with exceptions for small employers. In the years leading up to the passage of the ACA, about 14-16% of people in the United States were uninsured (across all ages). By 2023, the uninsured rate had fallen to a record low of 7.7%. Most of the gains in insurance coverage have come from the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid, followed by the creation of the exchange markets.

For people with private health insurance, the ACA also includes several consumer protections and market rules (discussed in more detail in the chapter on regulation of private insurance). For example, the ACA prohibits health plans from denying people coverage, charging them higher premiums, as well as rescinding or imposing exclusions to coverage due to preexisting health conditions. The ACA also prohibits annual and lifetime limits on the dollar amount of coverage and restricts the amount of out-of-pocket costs individuals and families may incur each year for in-network care. Additionally, the law requires most health plans to cover preventive health services with no out-of-pocket costs. Health insurers must also issue rebates to enrollees and businesses each year if they fail to meet Medical Loss Ratio standards. Moreover, people with private coverage can keep their young adult children on their health plan up to age 26.

The ACA imposes additional new regulations on private health plans sold to individuals and small businesses. These rules significantly limit the ways in which health plans can charge higher premiums. ACA-compliant health plans sold on the individual and small group markets can only vary premiums based on location, family size, tobacco use, and age (with older adults being charged no more than three times younger adults). This means that people with preexisting conditions cannot be charged higher premiums, nor can insurers charge higher rates based on gender or other factors. The ACA requires individual and small group insurers planning to increase premiums significantly to justify those rate increases publicly and also included grants for states to improve their rate review programs. The ACA also created risk programs in the individual and small group markets to mitigate adverse selection and to reduce health insurers’ incentives to avoid attracting sicker enrollees.

While Medicaid expansion is one of the most impactful provisions of the ACA, the law changed Medicaid in other ways too. For example, people gaining coverage through the Medicaid expansion are guaranteed a benchmark benefit package that covers essential health benefits. Furthermore, the ACA required state Medicaid programs to cover preventive services without cost sharing. The law also increased Medicaid payments to primary care providers, provided new options for states to cover in-home and community-based care, increased Medicaid drug rebates, and extended those rebates to Medicaid managed care plans.

The ACA also made a number of changes to Medicare. Notably, the ACA phased out the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit coverage gap (colloquially known as the “donut hole”) and provides preventive benefits for Medicare enrollees without cost-sharing. The ACA also includes several changes aimed at reducing the growth in Medicare spending. For example, the ACA includes reductions in the growth of Medicare payments to hospitals and other providers, and to Medicare Advantage plans. The law also created an Innovation Center within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) tasked with developing and testing new health care payment and delivery models and established the Medicare Shared Savings Program, a permanent accountable care organization (ACO) program in traditional Medicare that offers financial incentives to providers for meeting or exceeding savings targets and quality goals.

Finally, the ACA includes many other provisions that do not relate directly to health coverage. For example, the ACA authorizes the Food and Drug Administration to approve generic versions of biologic drugs. There are also provisions that aim to reduce waste and fraud, expand the health care workforce, increase data collection and reporting on health disparities, and improve public health preparedness.

When passed, the ACA was designed to be budget neutral, with health insurance subsidies and expansions of public programs financed through a variety of taxes and fees on individuals, employers, insurers, and certain businesses in the health sector, as well as savings from the Medicare program. As discussed in more detail below, some of these taxes or fees have since been repealed or reduced to zero dollars, including the individual mandate penalty, the medical device tax, and the so-called “Cadillac Tax,” which would have imposed an excise tax on high-cost employer health plans. Additionally, at times, a tax on health insurance carriers has been temporarily put on hold.

Health Insurance Marketplaces (also known as exchanges) are organizations set up to create more organized and competitive markets for individuals and families buying their own health insurance. The Marketplaces offer a choice of different health plans, certify plans that participate, and provide information and in-person assistance to help consumers understand their options and apply for coverage. Premium and cost-sharing subsidies based on income are available through the Marketplace to make coverage more affordable for individuals and families. People with very low incomes can also find out if they are eligible for coverage through Medicaid and CHIP while shopping on the Marketplace.

Some small businesses can buy coverage for their employees through separate exchanges called Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) Marketplace plans, but this chapter focuses primarily on the Marketplaces for individuals and families.

There is a health insurance Marketplace in every state for individuals and families and for small businesses. Some enrollment websites are operated by the state government or quasi-governmental bodies at the state level and have a special state name (such as Covered California or The Maryland Health Benefit Exchange). In 29 states where the federal government runs the enrollment website, it is called HealthCare.gov. As of early 2024, three state-based Marketplaces (Arkansas, Georgia, and Oregon) use the federal platform.

The Marketplaces exist alongside other coverage that is also sold to individuals or small businesses. The Marketplaces for individuals and families are part of what is called the “individual insurance market,” which also includes ACA-compliant and non-compliant insurance sold off the Marketplace (also called off-exchange coverage). Similarly, the “small group insurance market” includes the SHOP Marketplace plans as well as other ACA-compliant and non-compliant coverage sold to small businesses.

While many Americans are allowed to purchase unsubsidized coverage on the ACA Marketplaces, these markets primarily exist to fill a gap in coverage options for people who cannot get insurance through work or public programs. Some people who sign up for Marketplace coverage are unemployed or between jobs, while others are students, self-employed or work at businesses that do not offer coverage (e.g. very small companies) or offer coverage that is deemed unaffordable.

To receive the premium tax credit for coverage starting in 2024, a Marketplace enrollee must meet the following criteria:

Employer coverage: If a person’s employer offers health coverage but that coverage is deemed unaffordable or of insufficient value, the employee and/or their family may be able to receive subsidies to buy Marketplace coverage. Employer coverage is considered affordable if the required premium contribution is no more than 8.39 percent of household income in 2024. The Marketplace will look at both the required employee contribution for self-only and (if applicable) for family coverage. If the required employee contribution for self-only coverage is affordable, but the required employee contribution for family coverage is more than 8.39 percent of household income, the dependents can purchase subsidized exchange coverage while the employee stays on employer coverage.

The employer’s coverage must also meet a minimum value standard that requires the plan to provide substantial coverage for physician services and for inpatient hospital care with an actuarial value of at least 60 percent (meaning the plan pays for an average of at least 60 percent of all enrollees’ combined health spending, similar to a bronze plan). The plan must also have an annual OOP limit on cost sharing of no more than $9,450 for self-only coverage and $18,900 for family coverage in 2024.

People offered employer-sponsored coverage that fails to meet either the affordability threshold or minimum value requirements can qualify for Marketplace subsidies if they meet the other criteria listed above.

Eligibility for Medicaid: In states that have expanded Medicaid under the ACA, adults with income up to 138 percent FPL are generally eligible for Medicaid and, therefore, are ineligible for Marketplace subsidies. In the states that have not adopted the Medicaid expansion, adults with income as low as 100 percent of poverty can qualify for Marketplace subsidies, but those with lower incomes are not eligible for tax credits and generally not eligible for Medicaid unless they meet other state eligibility criteria.

An exception to the rule restricting tax credit eligibility for adults with income below the poverty level is made for certain lawfully present immigrants. Other federal rules restrict Medicaid eligibility for lawfully present immigrants, other than pregnant women, refugees, and asylees, until they have resided in the U.S. for at least five years. Immigrants who would otherwise be eligible for Medicaid but have not yet completed their five-year waiting period may instead qualify for tax credits through the Marketplace. If an individual in this circumstance has an income below 100 percent of poverty, for the purposes of tax credit eligibility, their income will be treated as though it is equal to the poverty level. Immigrants who are not lawfully present are generally ineligible to enroll in health insurance through the Marketplace, receive tax credits through the Marketplaces, or enroll in non-emergency Medicaid and CHIP.

The ACA requires all qualified health benefits plans to cover essential health benefits, including those offered through the Marketplaces and those offered in the individual and small group markets off-exchange. Grandfathered individual and employer-sponsored plans (which existed before the ACA was passed) and non-compliant plans (which include short-term plans) do not have to cover essential health benefits.

The law specifies that the essential health benefits package must include at least 10 categories of items and services: ambulatory patient services; emergency services; hospitalization; pregnancy, maternity, and newborn care; mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment; prescription drugs; rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices; laboratory services; preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management; and pediatric services, including oral and vision care. It also requires that the scope of benefits be equal to that of a “typical employer plan.”

These categories are broad and subject to interpretation. For example, there could be limits on the number of physical therapy services an enrollee receives in a year. For more specific guidance on how to interpret these requirements, the federal government allows states to select a “benchmark” health plan (often one that was already offered to small businesses) as a standard.

Essential health benefits are a minimum standard. Plans can offer additional health benefits, like vision, dental, and medical management programs (for example, for weight loss). The ACA prohibits abortion coverage from being required as part of the essential health benefits package. The premium subsidy does not cover non-essential health benefits, meaning that people enrolling in a plan with non-essential benefits may have to pay a portion of the premium for these additional benefits.

Although plans must cover essential health benefits, they are allowed to apply cost sharing (deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance). This means enrollees may still face some out-of-pocket costs when receiving these services. However, preventive health services are required to be covered without cost sharing. Examples of preventive health services include vaccinations, cancer screenings, and birth control.

There are two types of financial assistance available to Marketplace enrollees. The first type, called the premium tax credit (or premium subsidy), reduces enrollees’ monthly payments for insurance coverage. The second type of financial assistance, the cost-sharing reduction (CSR), reduces enrollees’ deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs when they go to the doctor or have a hospital stay. To receive either type of financial assistance, qualifying individuals and families must enroll in a plan offered through a health insurance Marketplace. In addition to the federal subsidies discussed here, some states that operate their own exchange markets offer additional state-funded subsidies that further lower premium payments and/or deductibles or other forms of cost-sharing.

Premium Subsidies

Premium tax credits can be applied to Marketplace plans in any of four “metal” levels of coverage: bronze, silver, gold, and platinum. Bronze plans tend to have the lowest premiums but have the highest deductibles and other cost sharing, leaving the enrollee to pay more out-of-pocket when they receive covered health care services, while platinum plans have the highest premiums but very low out-of-pocket costs. There are also catastrophic plans, usually only available to younger enrollees, but the subsidy cannot be used to purchase one of these plans.

The premium tax credit works by limiting the amount an individual must contribute toward the premium for the “benchmark” plan – or the second-lowest cost silver plan available to the individual in their Marketplace. This “required individual contribution” is set on a sliding income scale. In 2024, for individuals with income up to 150 percent FPL, the required contribution is zero, while at an income of 400 percent FPL or above, the required contribution is 8.5 percent of household income.

These contribution amounts were set by the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in 2021 and temporarily extended by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) through the end of 2025. Prior to the ARPA, the required contribution percentages ranged from about two percent of household income for people with poverty level income to nearly 10 percent for people with income from 300 to 400 percent of poverty. Before the ARPA was passed, people with incomes above 400 percent of poverty were not eligible for premium tax credits. If Congress does not act to extend the IRA subsidies before the end of 2025, they will expire, and the original ACA premium caps will return.

The amount of tax credit is calculated by subtracting the individual’s required contribution from the actual cost of the “benchmark” plan. So, for example, if the benchmark plan costs $6,000 annually, the required contribution for someone with an income of 150 percent FPL is zero, resulting in a premium tax credit of $6,000. If that same person’s income equals 250 percent FPL (or $36,450 in 2024), the individual contribution is four percent of $36,450, or $1,458, resulting in a premium tax credit of $4,542.

The premium tax credit can then be applied toward any other plan sold through the Marketplace (except catastrophic coverage). The amount of the tax credit remains the same, so a person who chooses to purchase a plan that is more expensive than the benchmark plan will have to pay the difference in cost. If a person chooses a less expensive plan, such as the lowest-cost silver plan or a bronze plan, the tax credit will cover a greater share of that plan’s premium and possibly even the entire cost of the premium. When the tax credit exceeds the cost of a plan, it lowers the premium to zero and any remaining tax credit amount is unused.

As mentioned above, the premium tax credit will not apply for certain components of a Marketplace plan premium. First, the tax credit cannot be applied to the portion of a person’s premium attributable to covered benefits that are not essential health benefits (EHB). For example, a plan may offer adult dental benefits, which are not included in the definition of EHB. In that case, the person would have to pay the portion of the premium attributable to adult dental benefits without financial assistance. In addition, the ACA requires that premium tax credits may not be applied to the portion of premium attributable to “non-Hyde” abortion benefits. Marketplace plans that cover abortion are required to charge a separate minimum $1 monthly premium to cover the cost of this benefit; this means a consumer who is otherwise eligible for a fully subsidized, zero-premium policy would still need to pay $1 per month for a policy that covers abortion benefits. Finally, if the person smokes cigarettes and is charged a higher premium for smoking, the premium tax credit is not applied to the portion of the premium that is the tobacco surcharge.

Cost-Sharing Reductions

The second form of financial assistance available to Marketplace enrollees is a cost-sharing reduction. Cost-sharing reductions lower enrollees’ out-of-pocket cost due to deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance when they use covered health care services. People who are eligible to receive a premium tax credit and have household incomes from 100 to 250 percent of poverty are eligible for cost-sharing reductions.

Unlike the premium tax credit (which can be applied toward any metal level of coverage), cost-sharing reductions (CSR) are only offered through silver plans. For eligible individuals, cost-sharing reductions are applied to a silver plan, essentially making deductibles and other cost sharing under that plan more similar to that under a gold or platinum plan. Individuals with income between 100 and 250 percent FPL can continue to apply their premium tax credit to any metal level plan, but they can only receive the cost-sharing subsidies if they pick a silver-level plan.

Cost-sharing reductions are determined on a sliding scale based on income. The most generous cost-sharing reductions are available for people with income between 100 and 150 percent FPL. For these enrollees, silver plans that otherwise typically have higher cost sharing are modified to be more similar to a platinum plan by substantially reducing the silver plan deductibles, copays, and other cost sharing. For example, in 2024, the average annual deductible under a silver plan with no cost-sharing reduction is over $5,000, while the average annual deductible under a platinum plan was $97. Silver plans with the most generous level of cost-sharing reductions are sometimes called CSR 94 silver plans; these plans have 94 percent actuarial value (which represents the average share of health spending paid by the health plan) compared to 70 percent actuarial value for a silver plan with no cost-sharing reductions.

Somewhat less generous cost-sharing reductions are available for people with income greater than 150 and up to 200 percent FPL. These reduce cost sharing under silver plans to 87 percent actuarial value (CSR 87 plans). In 2024, the average annual deductible under a CSR 87 silver plan was about $700.

For people with income greater than 200 and up to 250 percent FPL, cost-sharing reductions are available to modestly reduce deductibles and copays to 73 percent actuarial value (sometimes called CSR 73 plans). In 2024, the average annual deductible under a CSR 73 silver plan was about $4,500.

Insurers have flexibility in how they set deductibles and copays to achieve the actuarial value under Marketplace plans, including CSR plans, so actual deductibles may vary from these averages.

The ACA also requires maximum annual out-of-pocket spending limits on cost sharing under Marketplace plans, with reduced limits for CSR plans. In 2024, the maximum OOP limit is $9,450 for an individual and $18,900 for a family for all QHPs. Lower maximum OOP limits are permitted under cost-sharing reduction plans.

Cost-sharing reductions work differently for Native American and Alaska Native members of federally recognized tribes. For these individuals, cost-sharing reductions are available at higher incomes and can be applied to metal levels other than silver plans.

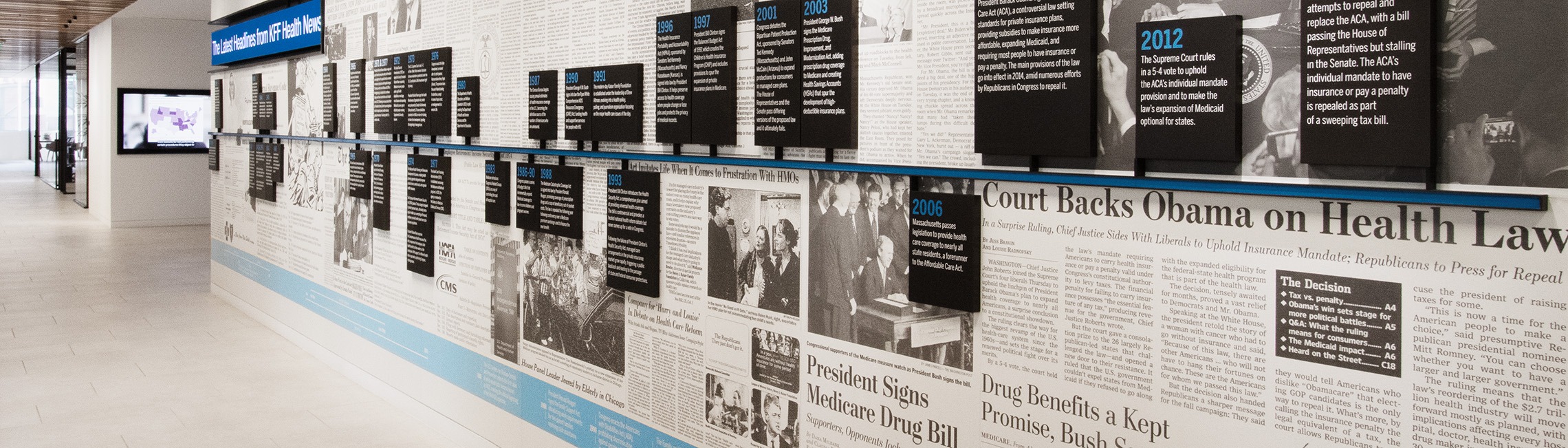

Since it was first signed into law, the ACA has undergone many changes through regulation, legislation, and legal challenges. Some provisions never got off the ground, and others were repealed, while more recent changes have expanded and enhanced other provisions. This section summarizes some of the most significant changes to the law.

Medicaid Expansion: The ACA originally expanded Medicaid to all non-Medicare eligible individuals under age 65 with incomes up to 138% of the poverty level. A Supreme Court ruling on the constitutionality of the ACA upheld the Medicaid expansion, but limited the ability of HHS to enforce it, thereby making the decision to expand Medicaid effectively optional for states. As of the beginning of 2024, 40 states and the District of Columbia had expanded Medicaid. Additionally, while not taking up Medicaid expansion under the ACA, Wisconsin did increase Medicaid eligibility to 100% of the poverty level, which is where ACA Marketplace subsidy eligibility begins. In the remaining states that have not expanded Medicaid, an estimated 1.5 million people fall into the so-called Medicaid coverage gap, meaning their incomes are too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to qualify for ACA Marketplace subsidies. The federal government covers 90% of the cost of Medicaid expansion.

Individual Mandate: The ACA also originally included an “individual mandate” or requirement for most people to maintain health insurance. In health insurance systems designed to protect people with pre-existing conditions and guarantee availability of coverage regardless of health status, countervailing measures are also needed to ensure people do not wait until they are sick to sign up for coverage, as doing so would drive up premiums. The ACA included a variety of these countervailing measures, with both “carrots” (e.g., premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions) and “sticks” (e.g., the individual mandate penalty and limited enrollment opportunities) to encourage healthy as well as sick people to enroll in health insurance coverage.

American citizens and U.S. residents without qualifying health coverage had to pay a tax penalty of the greater of $695 per year up to a maximum of three times that amount ($2,085) per family or 2.5% of household income. The penalty was set to increase annually by the cost-of-living adjustment. Exemptions were granted for financial hardship, religious objections, American Indians, those without coverage for less than three months, undocumented immigrants, incarcerated individuals, those for whom the lowest cost plan option exceeds 8% of an individual’s income, and those with incomes below the tax filing threshold.

Despite the popularity of the ACA’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions, the individual mandate was politically controversial and consistently viewed negatively by a substantial share of the public. In early 2017, under President Trump, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) stopped enforcing the individual mandate penalty. After several attempts to repeal and replace the ACA stalled out in the summer of 2017, Congress reduced the individual mandate penalty to $0, effective in 2019, as part of tax reform legislation passed in December 2017.

Cost-Sharing Reduction Payments: The ACA originally included two types of payments to insurers participating in the ACA Marketplace. First, insurers received advanced payments of the premium tax credit to subsidize monthly premiums for people buying their own coverage on the Marketplace. Second, insurers were required to reduce cost sharing (i.e., deductibles, copayments, and/or coinsurance) for low-income enrollees and the federal government was required to reimburse insurers for these cost-sharing reductions (CSRs). However, the funds for the payment of cost-sharing reductions were never appropriated. The Trump administration ended federal CSR payments to insurers weeks before ACA Marketplace Open Enrollment for 2018 coverage began. In response to this, most states allowed insurers to compensate for the lack of government payments by raising premiums. At the time, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated termination of CSR payments to insurers would increase the federal deficit by $194 billion over 10 years, because of these higher premiums and corresponding increased premium tax credit subsidies. Although the CSR payments have ceased, cost-sharing reduction plans continue to be available to low-income Marketplace enrollees.

Enhanced and Expanded ACA Marketplace Subsidies: Another controversial aspect of the ACA was the so-called “subsidy cliff,” where people with incomes over 400% of the federal poverty level were ineligible for financial assistance on the Marketplace and, therefore, would have to pay a large share of their household income for unsubsidized health coverage. As a result, many middle-income people were being priced out of ACA coverage. The March 2021 COVID-19 relief legislation, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), extended eligibility for ACA health insurance subsidies to people with incomes over 400% of poverty buying their health coverage on the Marketplace. The ARPA also increased the amount of financial assistance for people with lower incomes who were already eligible under the ACA, making many low-income people newly eligible for free or nearly free coverage. Both provisions were temporary, lasting for two years, but the Inflation Reduction Act extends those subsidies through the end of 2025.

Family Glitch: Financial assistance to buy health insurance on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces is primarily available for people who cannot get coverage through a public program or their employer. Some exceptions are made, however, including for people whose employer coverage offer is deemed unaffordable or of insufficient value. For example, people can qualify for ACA Marketplace subsidies if their employer requires them to spend more than about 8-9% (indexed each year) of their household income on the company’s health plan premium. For many years, this affordability threshold was based on the cost of the employee’s self-only coverage, not the premium required to cover any dependents. In other words, an employee whose contribution for self-only coverage was less than the threshold was deemed to have an affordable offer, which means that the employee and their family members were ineligible for financial assistance on the Marketplace, even if the cost of adding dependents to the employer-sponsored plan would far exceed the approximately 8-9% of the family’s income. This definition of “affordable” employer coverage has come to be known as the “family glitch,” which affected an estimated 5.1 million people. Under a Biden administration federal regulation, the worker’s required premium contributions for self-only coverage and for family coverage will be compared to the affordability threshold of approximately 8-9% of household income. If the cost of self-only coverage is affordable, but the cost for family coverage is not, the worker will stay on employer coverage while their family members can apply for subsidized exchange coverage.

Public Opinion: Americans’ views of the Affordable Care Act have evolved over time. From the time the ACA passed, to when the Marketplaces first opened in 2014, and through the months leading up to President Trump’s election in 2016, public opinion of the ACA was strongly divided and often leaned more negative than positive. Many individual provisions of the ACA, such as protections for people with preexisting conditions, were popular, but the individual mandate was particularly unpopular.

News coverage during the ACA Marketplaces’ early years often centered on the rocky rollout, from the early Healthcare.gov website glitches to skyrocketing premiums in subsequent years. Coverage in later years focused on how unprofitable insurers exited the market, leaving people in some counties at risk of having no Marketplace insurer—and thus, no Marketplace through which to access health insurance subsidies.

In 2017, then President Trump and Republicans in Congress attempted to repeal or fundamentally alter the ACA. As proposals to replace the ACA became more concrete, though, public support for the ACA, particularly among Democrats and Independents, began to grow. Ultimately, the only key aspect of the law that was removed was the penalty for not purchasing health insurance—now lowered to $0 as part of a tax reform package.

Following repeal efforts and the removal of the individual mandate penalty, as well as a stabilization of the ACA Marketplaces, public support for the law has continued to grow and is now solidly more positive than negative. Although this support remains divided by party lines, several Republican-led states have adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion through popular votes.