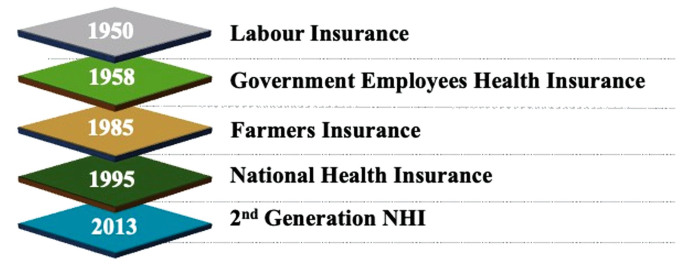

This chapter provides an overview of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) system. In 1995, major social insurance programmes, such as labour insurance, government employee health insurance and farmers’ insurance, were merged and enlarged to form the NHI to deliver universal health coverage. Since its inception, the payment system of the NHI is the fee-for-service method. Moreover, most of the health care is provided by private sectors, and there are no restrictions on patients seeking medical care. Owing to the high medical accessibility, the volume of outpatient services is high, and the National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) has to develop various measures to maintain its financial stability. Several strategies have been implemented by the NHIA for health equity, and the NHI MediCloud system, the NHI card and ‘My Health Bank’ were provided to ensure patients’ safety and enhance healthcare quality.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) programme was launched on 1 March 1995 to provide healthcare insurance for all residents. Over 23 million people are living in Taiwan, and over 16% of the population is over the age of 65. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita of Taiwan exceeded US$ 28,000 in 2020, and the total health expenditure was 6.54% of GDP in 2019. The life expectancy in Taiwan was 84.7 years for women and 78.1 years for men in 2020 (Table 1.1).

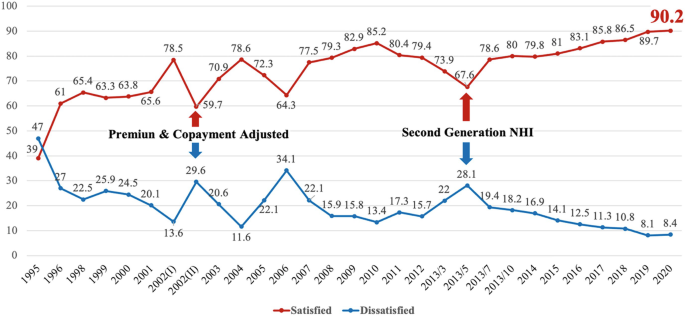

Since the NHI was established, the health component of the aforementioned insurances’ healthcare plans was consolidated into the NHI to provide nationwide health protection to Taiwan’s citizens and international residents. To improve the quality of health care, ensure the soundness of finance and encourage public participation, ‘the second-generation NHI’ was launched on 1 January 2013.

The National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) was previously known as the ‘Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, Executive Yuan’. When the Bureau was merged in 1995, only approximately 59% of the citizens were eligible to participate in the three major occupation-based medical insurance systems—labour insurance, farmers’ insurance and government employee health insurance. In line with the principles of financial sustainability and caring for the disadvantaged, these insurance systems were merged and enlarged to become a social insurance system to cover everyone. The Bureau of NHI was repositioned in 2010 as an ‘administrative agency’ and renamed the NHIA in 2013.

The NHI is a government-run social insurance scheme and is governed by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW). The MOHW established the NHI Committee to assist with the planning of NHI policies and supervise the implementation of insurance matters. It also established the NHI Mediation Committee to handle disputes concerning health insurance. As the insurer, the NHIA bears responsibility for NHI operations, healthcare quality and information management, research and development as well as personnel training. Administrative funding is provided by the central government through a budgetary process.

To effectively promote various NHI services, in addition to establishing specialised departments and offices for various services and policy promotions, the NHIA has also established six regional divisions throughout Taiwan, which directly handle underwriting, insurance premium collection, medical expense review and approval as well as the management of contracted medical institutions. Moreover, the NHIA has established 22 contact offices to serve the local residents. As of 30 June 2020, the NHIA had 3125 employees (Fig.1.2).

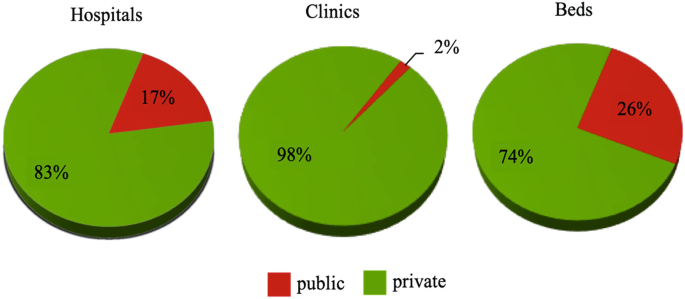

Taiwan’s healthcare system is dominated by the private sector. Hospitals adopt the closed-staff model, and physicians are primarily paid by hospitals (Fig. 1.3). There is no gatekeeper system to screen patients. Patients can go to any clinic or directly visit a hospital without a referral. Thus, the volume of hospital outpatient services is high. However, health care is usually provided promptly, and waiting time is negligible.

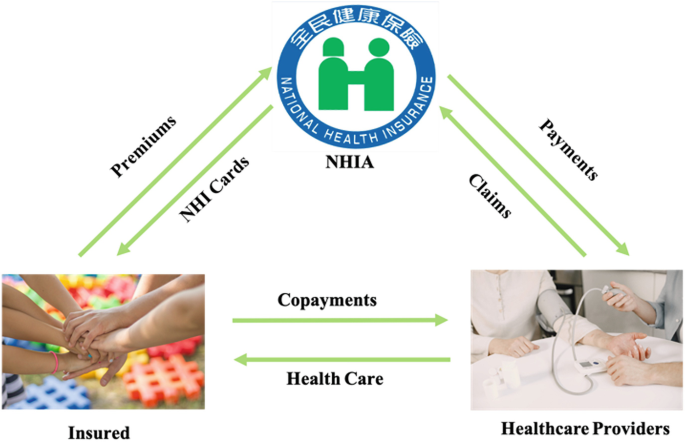

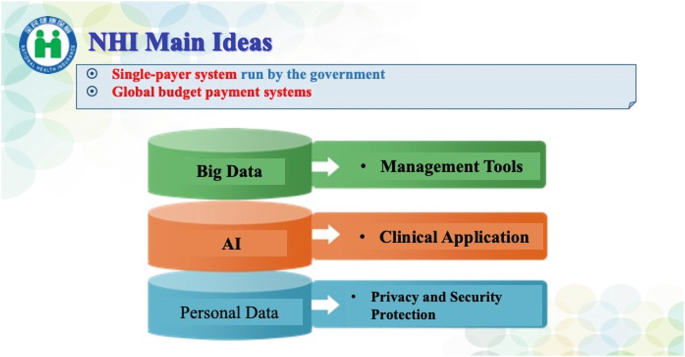

The NHI is a compulsory programme that all citizens and legal residents must join. The NHIA is the only agency authorised to administer the programme, which means that Taiwan’s NHI is a single-payer system run by the government. The NHIA collects premiums from the insured, their employers and the government. Premiums comprise 89% of the NHI revenues, out of which the government share is 36% according to the NHI Act. Moreover, the insured make co-payments when using healthcare services and the healthcare providers file claims with the NHIA for reimbursement (Fig. 1.4).

Although it is voluntary for healthcare providers to participate in this programme, about 93% of providers nationwide have joined the NHI. Providers are reimbursed according to plural payment programmes under the global budget payment system. Premium subsidies and co-payment waivers have been granted to the disadvantaged through different projects.

As discussed in detail in Chap. 2, the NHI is primarily financed through premiums, including general and supplementary premiums.

Each person remits the general premium according to the premium formula or the fixed figures. The insured are grouped into six categories and are subject to different premium calculation bases and contribution shares, depending on the category that they belong to. Most salaried employees have to pay 30% of their premiums, with their employers paying 60% and the government paying the remaining 10%. The government subsidises 100% of the premiums for low-income households and military conscripts. Inmates are also covered under the NHI, and their premiums are paid by the government.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, salary income as a percentage of national income declined, making premium growth lag behind income growth, thereby leading to funding shortfalls. The introduction of the supplementary premium on various types of incomes, other than regular payroll, has alleviated the perennial financial problems. Since 2013, in addition to the general premium, a supplementary premium has also been collected. The insured are charged a supplementary premium of 2.11% on certain incomes they receive, including large bonuses, professional fees, part-time wages, stock dividends, interest income and rental income.

The NHI provides comprehensive benefits that cover inpatient care, outpatient care, drugs, dental services, traditional Chinese medicine, day care for the mentally ill and home-based medical care. Moreover, expensive health services, such as dialysis and organ transplants, are all covered.

The insured make co-payments for their outpatient care to avoid the unnecessary utilisation of medical resources. The co-payment is partially waived if the outpatient visit is arranged by a referral. To ensure that people who need health care are not denied access because of the cost-sharing mechanism, individuals who meet certain conditions are exempt from co-payments, such as patients with catastrophic diseases, child delivery, medical services offered in mountain areas or on offshore islands, low-income households, veterans, children under the age of 3, as well as those who are insured but are in areas with insufficient medical resources.

If those insured have to stay in a hospital because of medical factors, they will be charged a co-insurance, and the rate varies depending on the length of stay. However, in 2021, this co-insurance was capped at around US$ 1400 per stay for the same disease and an accumulated total of US$ 2400, regardless of the disease.

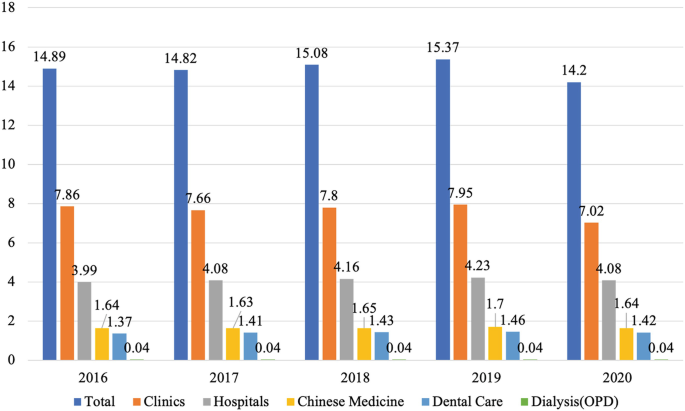

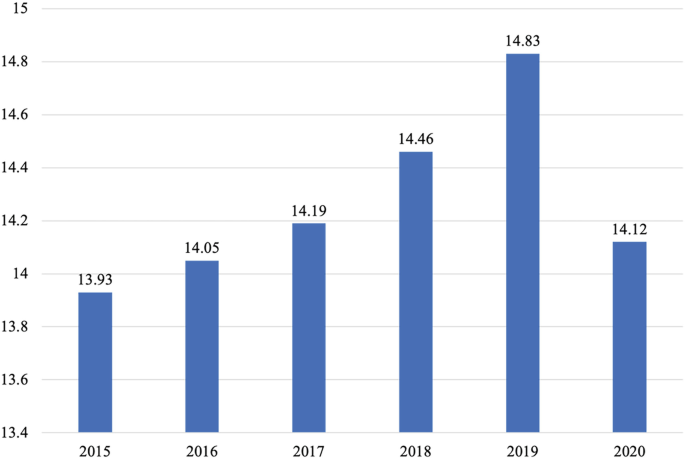

The average utilisation rate of the NHI outpatient services in 2020 was 14.2 visits per person (Fig. 1.5), including visits for dental care and traditional Chinese medicine. For inpatient care, the average utilisation rate was 14.12 admissions per 100 persons in 2020 (Fig. 1.6). The number of outpatient visits is substantially higher than that of many Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries.

When the NHI system was initiated, it sought to quickly integrate the existing civil service, labour and farmers’ insurance systems. The fee-for-service approach was adopted as the primary payment system. Moreover, using the government and labour insurance payment standards as the basis, the NHI’s payment standards were revised, and the scope of reimbursements and recommendations of medical groups were adjusted. However, this system resulted in an uncontrolled increase in medical expenses and has affected the quality of care. The NHIA has followed the example of other leading countries by designing different payment methods based on the characteristics of different types of medical care. The NHIA built the global budget payment systems, including global budgets for dental care, Chinese medicine, clinics, hospitals and dialysis. To further rationalise the reimbursement of health services, a resource-based relative value scale and a Taiwanese version of diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) were initiated in 2004 and 2010 respectively. The payment system of the NHI is discussed in more detail in Chap. 3.

To enhance the quality of health care, various projects addressing different needs have been implemented to offer adequate health care. For example, the Integrated Delivery System Plan, which was initiated in 1999, has improved health care in mountainous areas and on offshore islands by encouraging hospitals to dispatch doctors to these areas. This Integrated Delivery System Plan provides health care to 50 remote areas and serves about 480,000 people each year. In addition, different pay-for-performance projects have been implemented for certain diseases since 2001. Furthermore, patient-centred projects are effective to make patients easily access the health care they need.

For those who are less fortunate, the government provides several types of assistance, such as premium subsidies, financial assistance for the poor and medical assistance for the disadvantaged, to make sure that they have access to medical services. In addition, the policy of unlocking NHI cards removes the fetters imposed on financially disadvantaged people who fear seeking medical care because of overdue premium payments. One of the core values of Taiwan’s NHI programme is to remove financial barriers in health care for people through the NHI fund. This explains why the NHI can cover catastrophic diseases, such as haemophilia, which makes a patient cost 97 times as much as the average patient. The strategies for pursuing health equity through the NHI will be introduced in Chap. 5.

The NHI MediCloud system provides medical professionals with patients’ medical data to ensure drug safety and enhance healthcare quality. Medical professionals use the system online to view patients’ previous important data and images when patients visit them or are hospitalised. Medical professionals can read patients’ records of medications, surgeries, tests and exams, medical images, history of drug allergies, etc., through a secure virtual private network.

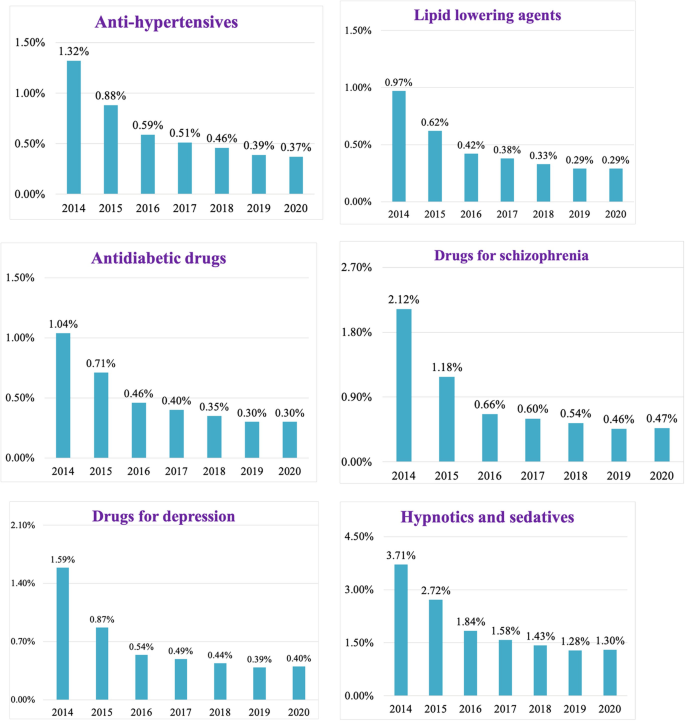

Figure 1.7 depicts the reduction rates of overlapping medication with the use of the NHI MediCloud system. In terms of overlapping days, the prescriptions of six selected drugs for chronic diseases with the same pharmacological action have significantly decreased by over half from 2014 to 2020, resulting in not only a savings of more than US$ 10 million but also making patients safer.

Furthermore, the NHI MediCloud system can improve the utilisation efficiency of medical resources. Physicians can view patients’ medical images, such as computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), X-rays, ultrasound images and endoscopic images, uploaded by other healthcare providers.

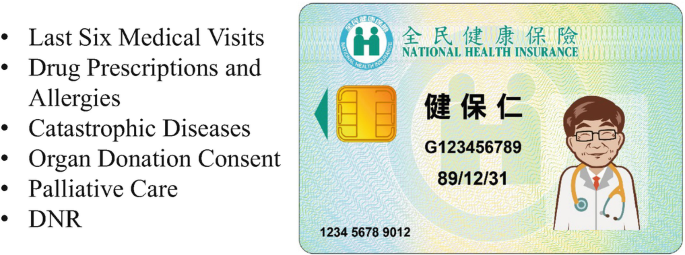

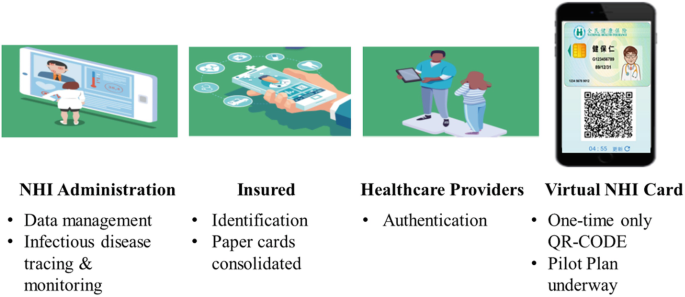

Smart card technology has been adopted since 1 January 2004. The NHI card contains records of a patient’s last six visits, drug prescriptions, drug allergies, catastrophic diseases, consent for organ donation, consent to palliative care and consent to a ‘Do not resuscitate’ (DNR) order (Fig. 1.8). The NHI card can also be used to monitor high-utilisation patients and detect fraud by analysing data that are uploaded daily. It can also help to identify potential carriers of communicable diseases in major epidemic outbreaks. Over the years, cloud computing technology has also been applied to give the card additional and more powerful functions, and the Virtual NHI Card Pilot Plan is also underway (Fig. 1.9).

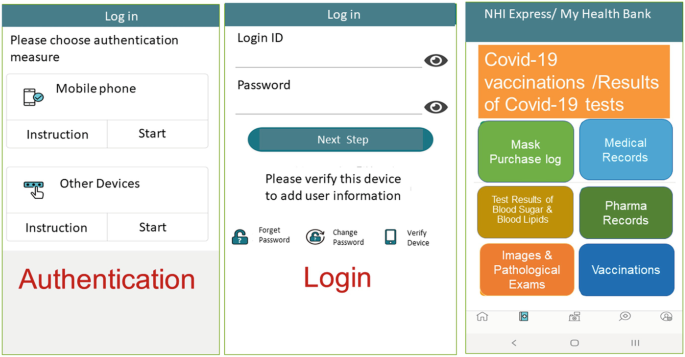

To heighten awareness of self-care and preventive health care, ‘My Health Bank’ was established. People can initiate their ‘My Health Bank’ account by authenticating themselves on a mobile phone or computer to access their health data anytime anywhere. ‘My Health Bank’ provides people with 3 years of medical data, medication records, test and exam results, vaccination records, as well as other useful services, including online named-based medical mask purchases (Fig. 1.10).

To prevent COVID-19 from spreading to communities during its early phase, since January 2020, the NHI MediCloud system has served as a real-time alert for healthcare providers. For any person with defined conditions, including foreign travel history, designated occupation, contact with a COVID-19 patient and a specific clustering situation, the NHI MediCloud system allows healthcare providers to obtain these data in real time and pay the costs for health care, enabling efficient triage as well as rapid and accurate diagnoses.

Moreover, the NHI card is used for name-based medical mask purchase. People can go to pharmacies to buy government-supplied medical masks with their NHI cards. This system helped people to have access to medical masks at the beginning of the pandemic when there was a shortage of medical masks. The NHIA also releases data on mask sales timely to cooperate with non-profit groups to update their ‘mask purchase map’ apps. The NHIA also analyses and provides medical data to Taiwan’s Centers for Disease Control, MOHW for pandemic surveillance (Table 1.2).

The NHI has safeguarded the health of all nationals and residents since its inception. People are insured to have easy access to healthcare providers regardless of their ability to pay. The NHI has not only established a secure healthcare network for all residents in Taiwan but is also well-known internationally for achieving universal health coverage and providing comprehensive health care at an affordable cost. Public satisfaction is also high, and medical quality is assured.

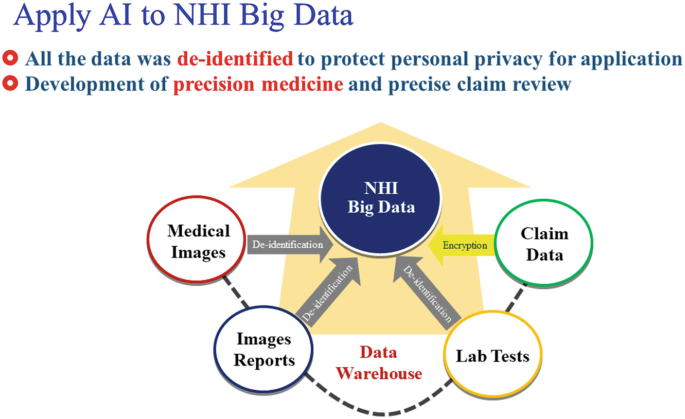

The NHI plays a crucial role in improving people’s health in Taiwan and has been sharing its successful experience with the rest of the world. However, the challenges it faces include rising life expectancies, increased prevalence of chronic diseases, technological advancement, as well as new drugs, which stimulate more innovative solutions. Therefore, ‘My Health Bank’ and the NHI MediCloud system were established to ensure the quality of health care and strengthen people’s health. Furthermore, virtual NHI card and AI technology are currently applied to some pilot projects to achieve high-performing, efficient and secure operations .

The outbreak of coronavirus disease has created a global health crisis that has had a deep impact on the way we perceive our world and everyday lives. Some countries were caught off guard by the sudden epidemic and struggled with disaster reduction. Taiwan employed the “National Health Insurance MediCloud System (NHI MediCloud System)” immediately as a platform to instantly update patient travel histories. This initial prevention measure received a positive response from the medical field. BMJ Opinion, the top international academic journal, published an article on 21 July 2020, titled “What we can learn from Taiwan’s response to the COVID-19 epidemic?”. It explained Taiwan’s use of medical information technology and comprehensive medical information to facilitate a farsighted project to face the contagious disease.

With the breakthroughs and continuous development of science and technology each year, an artificial intelligence (AI) wave has been sweeping the globe. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) system has accumulated a medical claims database for 27 years, which is the best foundation for developing AI applications and big data analyses for health care (Figs. 1.12 and 1.13) to gradually develop new medical economic models.

Taiwan has a strong and solid information technology background that can create a smart telemedicine model through information and communication network technology so that medical care is no longer limited by distance. In addition, “home-based medical care” is a new trend. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) encourages medical personnel to join the medical team. It is believed that more new medical technologies will be applied to home-based medical care in the future. Meanwhile, the NHIA has been establishing a new management system step by step.

Over the past two decades, although medical technology and equipment have progressed significantly, patients’ clinical conditions have become increasingly complex. This has led to relative increases in labour resource requirements in practising treatments. As a first step, the NHIA will review system fairness and payment standards.

Medical AI, precision medicine, new drugs, new medical devices and new medical technologies will provide medical care with a new economic model. These medical developments will affect medical management and new business strategies. “There is no chance to change without starting”. Our original goal at the outset, to provide the best medical care for 23 million people and create a happy working environment for the medical profession, will never change. We also hope that all medical partners can offer more health education to the public with their professional knowledge so that together, we can conserve the precious resources of the NHI system.

There is still much room for improvement in our system, but it cannot be rushed. After all, there are certain procedures for implementing new policies. With the following, I would like to provide, as a reference for all sectors, a list of unreasonable phenomena that must be dealt with in the future. In the meantime, I will contemplate how they can be improved and the suggestions I would make.